Espectacular video a Epecuén, la ciutat que es va inundar...

dimecres, 28 de maig del 2014

dimarts, 27 de maig del 2014

VOLTA A MENORCA 2014 - CAMI DE CAVALLS

Aquest cap de setmana a els Ermassets bike s'enfrontaven a una prova dura, dura de collons. Volta a Menorca en tres etapes, aahh!! i el que digui que Menorca és plana no té ni puta idea del que parla.

Divendres sortida en vaixell fins a l'illa, allà ens esperava Cristian per rodar amb nosaltres i fer d'cherpa i la seva germana per portar les maletes fins als hotels, des d'aquí donar-li un milió de gràcies per tot el que han fet per nosaltres.

sortida de Ciutadella sobre les 11:30 cap a Fornells, primera etapa, uns 64 km. per la costa nord, guapo, guapo però molt molt dura. Vam començar a rodar amb molta calor, aviat ens plantem és Punta Nati i Cala Morell, un paisatge pla però amb molta roca, el cul començava a picar i de valent, a partir de aquí la cosa es complica i molt un terreny molt dur, pujades brutals i baixades pitjors, a partir de mig camí la gent començava a patir la falta d'aigua i la calor.Les bicis aguantaven bé només un palier fluix de la bici de Rafael i algun parche que vam poder solucionar, dir que tota l'etapa és increïble, unes vistes, plajas i muntanyes que no es poden decribir amb paraules.

Arribada a Fornells a les 9 del vespre, hotel, dutxes, molta cervesa i sopar, aquesta etapa ens va deixar a tots uns més, uns menys tocats.

Segona etapa Fornells - Es Castell, uns 58 km., Per a alguns la més laight, etapa molt ràpida també recorre part de la costa interior de l'illa, cap problema greu, un basculant fluix i algun parche, Zero caigudes tot un deu.

Parem a dinar al Grau i des d'allà a pinyó fix fins Es Castell.

Tercera etapa Es Castell - Ciutadella , 79 km . , La més llarga .

Sortim ben aviat perquè havíem d'estar al port sobre les 18:30 . i simpre preocupa possibles problemes seriosos , també plovia i molt i això complica tot més . Aquesta etapa molt , molt ràpida , Es Castell - Son Bou , per carretera , fiiiiuuuu ! ! , Gaaasss ! ! , Gaassss ! i més gaaasss ! .

Arribada a Son Bou i retorn al Camí de Cavalls , gairebé tot costa, molta roca, gaasss , les bicis al límit , segueix plovent , basiots , fang i nosaltres estàvem mullats amb fang fins darrere de les orelles , un cristo , però nosaltres gasssssss .

He de dir que després de les dues etapes passades , la gent estava molt bé amb un terreny molt exigent per a nosaltres i per a les bicis , després de molts quilòmetres arribem a Cala Blanca , bruts com porcs , que vam fer doncs res , a nedar toca , l'aigua en un moment es va quedar marró , la gent ens mirava , debian de pensar - Que tropa .

Vam menjar en un restaurant increïble , paella i molta però molta cervesa , Molaaa molt, va ser un final d'aventura perfecte , més tard desprès del dinar arribada al port i tornada cap a casa .

Crec que tots els que hem rodat per aquesta increïble illa , ens ha deixat una experiència única tant a nivell esportiu com de companyerisme , UN CAP DE SETMANA 10 .

Vull donar les gràcies a tots els companys per tots els moments viscuts aquests tres dies increïbles , una gran experiència .

Ermassets BIKE , Molt per disfrutar

dilluns, 26 de maig del 2014

dijous, 15 de maig del 2014

Videos retro - Sprung 2 (1998)

Un d'aquests videos retro que val la pena mirar. Surten mites del btt quan encara no tenien barba fent desastres i pegant-se galetes de forma gratuïta.

dimecres, 14 de maig del 2014

Zumbi F-11 - Review

A dia d'avui queden poques marques que te permeten personalitzat la geometría d'una bici. Una d'aquestes és ZUMBI.

Noticia: Pinkbike.com

Theory

When it comes to geometry, it can be an incredibly personal thing dependent on your own body shape, strengths and both what and how you ride. Taken to extremes that means an average sized rider in stature may like anything from a small to a large, or maybe even an extra large frame. Where the difficulty lies in this is when you have to compromise in one area to get another right, and this is where the beauty of custom geometry comes in. Obviously it helps if you know what you want to start with, and as a couple of small tweaks in the wrong direction could easily create a monster; this could even be considered crucial. Enough experience on numerous bikes has led us to know exactly what we want, and with this in mind we set out to create the perfect big mountain enduro bike with Zumbi. It’s fairly safe to say that building a bike specifically for a couple of races can be considered a frivolous exercise but with the remit that we were going to be racing the Megavalanche and several big races in Europe that was our game plan. With these races in our sights it was fairly easy to remove the features from a bike that we knew we’d have no need for, and instead introduce those which we knew would be advantageous.

Geometry

So what did we go for in the end? In the months up to the meeting with Zumbi we had come to realise that a large frame was definitely better for our body geometry, with most mediums just beginning to feel a little cramped as trails got faster and bigger with the better ability of trail bikes. In addition to this we’d spent a little time in the company of a Mondraker Dune with its Forward Geometry. Both of these thoughts combined to convince us that an experiment was definitely worth the risk. So with the longer geometry feeling just right, and essentially giving us a bike with the downhill-on-a-diet feel, we set about sketching out our ideal dimensions. First up was head angle, and with 67 beginning to feel all too steep for our riding we settled on 65 degrees with a 160mm Fox 36 fork up front. Top tube was a fairly reachy 635mm, combining with fairly short 430mm chainstays to give us a wheelbase at a fraction over 1203mm. Those figures certainly aren’t going to win any points for low speed agility but then that was never the intention and the reward is better handling at higher speed. Where Mondraker choose to use a super short stem we reduced the top tube to give us a bit more stem choice as well as a lower front, and opted to build the bike up with the then brand new Burgtec 50mm trail stem. It sounds reachy, and it is unavoidably so when pedalling, but the low standover height takes away any of the normal challenges associated with larger frames. This allows you to get really aggressive with the bike, helping to negate some of the reduction in nimbleness at lower speeds while giving plenty of space to shift your weight around for subtle balance changes on rougher and faster ground.

The Suspension

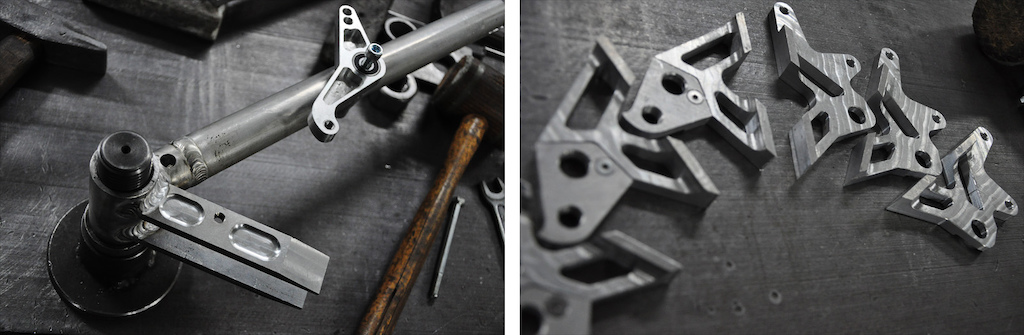

Move onto the heart of bike and you’ll see the FPS linkages marking the Floating Pivot Suspension system. There will of course be accusations that it looks like a DW link, but the similarity ends with the looks, because as with all of these designs which create a virtual pivot point (different than VPP) the key is in the angles of the linkages relative to each other and the resultant virtual pivot location. Dependent on your chosen emphasis, these linkages can be tuned to give different characteristics without drastically altering the physical design of the bike. On the F-11 the pivot is high and medium forward. With a 36T chainring this gave acceptable pedalling, and a suspension curve that ramped up noticeably, as can be seen in the second image, for both the 140mm and 165mm travel settings. This control was aided by a custom valved Fox CTD courtesy of Mojo, although stock bikes will come with the highly rated BOS Vip’r Air. When it comes to shock choice we were unfortunately somewhat limited to non-piggyback designs which is a shame as we were very keen to use the Float X, but Zumbi have now modified the design to accommodate even shocks as big as the Cane Creek Double Barrel Air. All said and done though, despite the slight disappointment in not using the Float-X, the CTD proved to be more than capable. Although a 165mm travel mode is available, we found that 140mm was perfectly sufficient for us and the advantage of this was that the shock wasn’t being worked so hard thanks to the slightly reduced leverage ratio. This only reinforced our belief in the performance that the rear end offered.

Other Features

Being offered a custom build is a great way to introduce features to a bike that you find missing on those mainstream models, or modify things to suit the gear you’re running. In our case that meant deciding on internal cable routing, a tapered head tube, and cables exiting the downtube to run along the chainstays for maximum protection. We also ensured that the frame was compatible for the Reverb Stealth although also included the necessary guides to run the Fox DOSS that we knew we’d initially be building the bike with. We’d initially been keen to go for the 142mm rear axle but the very short notice build meant that only 135mm rear triangles were available, which was a shame, but not a deal breaker by any means. The only slight irritation was having to find all the old 135mm adaptors long since retired to the spares box, but short notice is short notice and if a 142mm back end wasn’t available there wasn’t much we could do about it. ISCG 05 was of course in place instead of any front derailleur mounts or cable routing. This may be a little extreme for some but with an 11-36T cassette and a single 36T ring up front we’ve not found any issues in over two years of riding with this setup. So a chain device in place it is, although with the advent of thick/thin chainrings this will soon be changed to a taco style device with no true chain guide.

Ride Report

This is of course the primary concern above all else, and building it up in a side street of Les Deux Alpes was certainly a lesson in anticipation, matched with a little concern over how everything was going to piece together. We had literally thrown the boxes of new parts into the bike bag back home in Scotland, added a handful of tools, some spare bits we thought might come in handy and chucked it at the British Airways check-in crew at the airport. Nothing beats a lack of organisation for added stress. Luckily things went together reasonably easily, barring a few fruitful hunts for headset parts and hub adaptors which then led to the next concern; how would it ride? Jumping on it in the car park certainly gave us reason to be confident but a horizontal piece of tarmac is not a steep and rocky trail, so it was time to pick up the spare lift pass from the front of the van and go ride.

So just how well does the geometry work, and how does the back end deal with the trails we tested the bike on? Well first of all the length and slackness of the bike was immediately noticeable, and although we’ll separate out the suspension performance from the geometry the two are intrinsically linked, especially when it comes to stability. Our first rides were very much on what most riders would call big mountain terrain, with a combination of Les Deux Alpes and Alpe d’Huez trails rolling underneath the wheels. Rocks, braking bumps, narrow ruts, dust, wet grit; you name it and in our first week of riding we had the conditions. All those conditions combined with the amount of riding being done in a compressed space of time gave ample opportunity to get to grips with the bikes handling and set it up properly.

After a little experimentation we settled on 160psi in the rear shock with about 90psi in the fork for our 78kg clothed weight, pressures which were matched by reasonable use of the compression dials to keep control at both ends. In rebound, despite normally favouring a slower than slow setup on the rear shock we actually found that counterproductive on the F-11/CTD combination and settled for it slightly faster. In this way we still retained control in the first third of the travel to prevent any bucking but allowed the wheel to track the ground effectively the rest of the time. The fork was similarly sped up to match, taking them to the point where they were beginning to push wide before dialing back a few clicks to find the sweet spot. The ramp up of the spring curve was good enough to not notice any bottom out, harsh or otherwise, although the o-ring and swept area of the shock shaft indicated that we were using all available travel pretty regularly. The bike also felt consistent no matter what we were hitting with it, and this allowed us to continue pushing as hard as we dared, a great feature when you’re riding relatively unknown trails at speeds well beyond your ability to stop within your view. We’d certainly level some of that stability and consistency at both the wheelbase and head angle, both of which are firmly in downhill territory, but even so the bikes ability to deal with the rough was exemplary. And with mention of the geometry, how was that? On slower parts of the trails, and those who have ridden the Megavalanche before will know these bits, the length was definitely noticeable. Not so much that it was a hindrance, but you knew that you definitely needed to concentrate on your entry to the corner and get a little muscly to keep the bike working through. It definitely didn’t appreciate a t-bone as this lost the tractional advantage of that longer wheelbase and left you fighting to get that lost speed back. Through wheel sized braking bumps there were also noticeable improvements in fore/aft yaw, meaning you really could jump the bike into rough corners without fear of the front end tucking under. The ability of the bike to rail faster corners was also pretty much unhindered by mid-corner changes in surface or rocks, another element that allowed you to really trust what the bike would do in any given situation.

Since those alpine rides we’ve also had enough time to get used to it on our home trails of the Tweed Valley in Scotland. Replace rock with roots, dust with mud, and fast with steep and technical. In theory you would expect this to be the Achilles heel of a bike such as our custom F-11 but as with our first rides in the alps, we were shown just how capable a bike it is. We sped the shock up slightly to compensate for the lack of heat fade and felt perfectly comfortable getting aggressive with it from the start. Off camber traction is impressive, those supple initial few inches of travel providing enough give to keep the bike on an even keel even when the trail becomes greasy and interspersed with the white streaks of polished wet roots. Climbing is of course a slight disadvantage, and this was immediately apparent on our return from three weeks of riding with chairlifts. Not for the suspension, which while active seemed to suffer from absolutely minimal pedal input, but because the length of the front centre and head angle just put you in a less efficient place for it, and a place from which you can’t really escape. It’s not horrific by any means, and for us it is a worthwhile trade-off to gain so much more versatility and ability on descents, but it’s definitely a point worth noting if you’re considering the custom geometry route on any bike.

Issues

We’ve already touched on a few things that we would probably do differently given our time again, and we’ve also discussed changes with Pawel at Zumbi. Some of these are already in production. 142mm dropouts are now standard across both the 26” and 650B frames, and the shock baskets are now capable of accepting a Cane Creek DB Air shock which is about as large a shock as you’re ever likely to fit, doing away with the space issue we had when we wanted to fit a Fox Float-X to our bike. Another point we raised was that the taper headtube should also evolve from the external 1 1/8” and 1.5” cups on our frame to use the same ZS44/ZS56 semi-internal type headsets that have fast become almost standard across the industry. This is now standard on all new frames and allows for better internal cable routing as well as easing headset sourcing.

A final point we found was that, while absolutely fine for the original trail bike aims of the F-11, the shock mounting hardware and the lower linkage designs were both at their very limits when used for the bigger courses and we suffered a couple of bent bolts. It’s a point we’ve discussed at length already with Pawel at Zumbi and there are redesigns in course to eradicate these weaknesses. We believe the lower linkage issue to be down to the additional twisting forces brought upon it by the longer front end and the riding that we were therefore able to put it through. As with any small company development is ongoing and we certainly have no hesitation in believing that all these niggles are going to be resolved.

Pinkbike's take:

Review:

Zumbi F-11

BY Alasdair MacLennan

Zumbi might not be the name at the forefront of people’s minds when it comes to choosing a bike. But originating in the Polish town of Myslenice they are on the doorstep of some incredible riding and are brainchild of passionate owner, Pawel Matuszynski. Despite being a small company they have previously fielded a World Cup team, and continue to have a strong presence around the world. Tested here is their F-11, an enduro race-ready frameset custom tuned to our tastes. And when we say custom we do mean custom, for the geometry is all of our own choosing, a service that Zumbi are happy offering to any prospective purchaser. For those interested in the background of Zumbi, Pinkbike had an interview with Pawel late last year which can be found here.

|

Zumbi F-11 Details

• Intended use: all-mountain / enduro • Rear wheel travel: 140mm or 165mm • Wheel size: 26" • Aluminum frame • Custom geometry • FPS suspension design • Price: Frame only, $1800 USD, custom geometry adds $100 |

Theory

When it comes to geometry, it can be an incredibly personal thing dependent on your own body shape, strengths and both what and how you ride. Taken to extremes that means an average sized rider in stature may like anything from a small to a large, or maybe even an extra large frame. Where the difficulty lies in this is when you have to compromise in one area to get another right, and this is where the beauty of custom geometry comes in. Obviously it helps if you know what you want to start with, and as a couple of small tweaks in the wrong direction could easily create a monster; this could even be considered crucial. Enough experience on numerous bikes has led us to know exactly what we want, and with this in mind we set out to create the perfect big mountain enduro bike with Zumbi. It’s fairly safe to say that building a bike specifically for a couple of races can be considered a frivolous exercise but with the remit that we were going to be racing the Megavalanche and several big races in Europe that was our game plan. With these races in our sights it was fairly easy to remove the features from a bike that we knew we’d have no need for, and instead introduce those which we knew would be advantageous.

|

Ten years ago this would have been considered slack and long for even a downhill race bike. How times have changed - now even trail bikes have 65-degree head angles. Ten years ago this would have been considered slack and long for even a downhill race bike. How times have changed - now even trail bikes have 65-degree head angles. |

Geometry

So what did we go for in the end? In the months up to the meeting with Zumbi we had come to realise that a large frame was definitely better for our body geometry, with most mediums just beginning to feel a little cramped as trails got faster and bigger with the better ability of trail bikes. In addition to this we’d spent a little time in the company of a Mondraker Dune with its Forward Geometry. Both of these thoughts combined to convince us that an experiment was definitely worth the risk. So with the longer geometry feeling just right, and essentially giving us a bike with the downhill-on-a-diet feel, we set about sketching out our ideal dimensions. First up was head angle, and with 67 beginning to feel all too steep for our riding we settled on 65 degrees with a 160mm Fox 36 fork up front. Top tube was a fairly reachy 635mm, combining with fairly short 430mm chainstays to give us a wheelbase at a fraction over 1203mm. Those figures certainly aren’t going to win any points for low speed agility but then that was never the intention and the reward is better handling at higher speed. Where Mondraker choose to use a super short stem we reduced the top tube to give us a bit more stem choice as well as a lower front, and opted to build the bike up with the then brand new Burgtec 50mm trail stem. It sounds reachy, and it is unavoidably so when pedalling, but the low standover height takes away any of the normal challenges associated with larger frames. This allows you to get really aggressive with the bike, helping to negate some of the reduction in nimbleness at lower speeds while giving plenty of space to shift your weight around for subtle balance changes on rougher and faster ground.

The Suspension

Move onto the heart of bike and you’ll see the FPS linkages marking the Floating Pivot Suspension system. There will of course be accusations that it looks like a DW link, but the similarity ends with the looks, because as with all of these designs which create a virtual pivot point (different than VPP) the key is in the angles of the linkages relative to each other and the resultant virtual pivot location. Dependent on your chosen emphasis, these linkages can be tuned to give different characteristics without drastically altering the physical design of the bike. On the F-11 the pivot is high and medium forward. With a 36T chainring this gave acceptable pedalling, and a suspension curve that ramped up noticeably, as can be seen in the second image, for both the 140mm and 165mm travel settings. This control was aided by a custom valved Fox CTD courtesy of Mojo, although stock bikes will come with the highly rated BOS Vip’r Air. When it comes to shock choice we were unfortunately somewhat limited to non-piggyback designs which is a shame as we were very keen to use the Float X, but Zumbi have now modified the design to accommodate even shocks as big as the Cane Creek Double Barrel Air. All said and done though, despite the slight disappointment in not using the Float-X, the CTD proved to be more than capable. Although a 165mm travel mode is available, we found that 140mm was perfectly sufficient for us and the advantage of this was that the shock wasn’t being worked so hard thanks to the slightly reduced leverage ratio. This only reinforced our belief in the performance that the rear end offered.

Other Features

Being offered a custom build is a great way to introduce features to a bike that you find missing on those mainstream models, or modify things to suit the gear you’re running. In our case that meant deciding on internal cable routing, a tapered head tube, and cables exiting the downtube to run along the chainstays for maximum protection. We also ensured that the frame was compatible for the Reverb Stealth although also included the necessary guides to run the Fox DOSS that we knew we’d initially be building the bike with. We’d initially been keen to go for the 142mm rear axle but the very short notice build meant that only 135mm rear triangles were available, which was a shame, but not a deal breaker by any means. The only slight irritation was having to find all the old 135mm adaptors long since retired to the spares box, but short notice is short notice and if a 142mm back end wasn’t available there wasn’t much we could do about it. ISCG 05 was of course in place instead of any front derailleur mounts or cable routing. This may be a little extreme for some but with an 11-36T cassette and a single 36T ring up front we’ve not found any issues in over two years of riding with this setup. So a chain device in place it is, although with the advent of thick/thin chainrings this will soon be changed to a taco style device with no true chain guide.

Ride Report

This is of course the primary concern above all else, and building it up in a side street of Les Deux Alpes was certainly a lesson in anticipation, matched with a little concern over how everything was going to piece together. We had literally thrown the boxes of new parts into the bike bag back home in Scotland, added a handful of tools, some spare bits we thought might come in handy and chucked it at the British Airways check-in crew at the airport. Nothing beats a lack of organisation for added stress. Luckily things went together reasonably easily, barring a few fruitful hunts for headset parts and hub adaptors which then led to the next concern; how would it ride? Jumping on it in the car park certainly gave us reason to be confident but a horizontal piece of tarmac is not a steep and rocky trail, so it was time to pick up the spare lift pass from the front of the van and go ride.

So just how well does the geometry work, and how does the back end deal with the trails we tested the bike on? Well first of all the length and slackness of the bike was immediately noticeable, and although we’ll separate out the suspension performance from the geometry the two are intrinsically linked, especially when it comes to stability. Our first rides were very much on what most riders would call big mountain terrain, with a combination of Les Deux Alpes and Alpe d’Huez trails rolling underneath the wheels. Rocks, braking bumps, narrow ruts, dust, wet grit; you name it and in our first week of riding we had the conditions. All those conditions combined with the amount of riding being done in a compressed space of time gave ample opportunity to get to grips with the bikes handling and set it up properly.

After a little experimentation we settled on 160psi in the rear shock with about 90psi in the fork for our 78kg clothed weight, pressures which were matched by reasonable use of the compression dials to keep control at both ends. In rebound, despite normally favouring a slower than slow setup on the rear shock we actually found that counterproductive on the F-11/CTD combination and settled for it slightly faster. In this way we still retained control in the first third of the travel to prevent any bucking but allowed the wheel to track the ground effectively the rest of the time. The fork was similarly sped up to match, taking them to the point where they were beginning to push wide before dialing back a few clicks to find the sweet spot. The ramp up of the spring curve was good enough to not notice any bottom out, harsh or otherwise, although the o-ring and swept area of the shock shaft indicated that we were using all available travel pretty regularly. The bike also felt consistent no matter what we were hitting with it, and this allowed us to continue pushing as hard as we dared, a great feature when you’re riding relatively unknown trails at speeds well beyond your ability to stop within your view. We’d certainly level some of that stability and consistency at both the wheelbase and head angle, both of which are firmly in downhill territory, but even so the bikes ability to deal with the rough was exemplary. And with mention of the geometry, how was that? On slower parts of the trails, and those who have ridden the Megavalanche before will know these bits, the length was definitely noticeable. Not so much that it was a hindrance, but you knew that you definitely needed to concentrate on your entry to the corner and get a little muscly to keep the bike working through. It definitely didn’t appreciate a t-bone as this lost the tractional advantage of that longer wheelbase and left you fighting to get that lost speed back. Through wheel sized braking bumps there were also noticeable improvements in fore/aft yaw, meaning you really could jump the bike into rough corners without fear of the front end tucking under. The ability of the bike to rail faster corners was also pretty much unhindered by mid-corner changes in surface or rocks, another element that allowed you to really trust what the bike would do in any given situation.

Since those alpine rides we’ve also had enough time to get used to it on our home trails of the Tweed Valley in Scotland. Replace rock with roots, dust with mud, and fast with steep and technical. In theory you would expect this to be the Achilles heel of a bike such as our custom F-11 but as with our first rides in the alps, we were shown just how capable a bike it is. We sped the shock up slightly to compensate for the lack of heat fade and felt perfectly comfortable getting aggressive with it from the start. Off camber traction is impressive, those supple initial few inches of travel providing enough give to keep the bike on an even keel even when the trail becomes greasy and interspersed with the white streaks of polished wet roots. Climbing is of course a slight disadvantage, and this was immediately apparent on our return from three weeks of riding with chairlifts. Not for the suspension, which while active seemed to suffer from absolutely minimal pedal input, but because the length of the front centre and head angle just put you in a less efficient place for it, and a place from which you can’t really escape. It’s not horrific by any means, and for us it is a worthwhile trade-off to gain so much more versatility and ability on descents, but it’s definitely a point worth noting if you’re considering the custom geometry route on any bike.

Issues

We’ve already touched on a few things that we would probably do differently given our time again, and we’ve also discussed changes with Pawel at Zumbi. Some of these are already in production. 142mm dropouts are now standard across both the 26” and 650B frames, and the shock baskets are now capable of accepting a Cane Creek DB Air shock which is about as large a shock as you’re ever likely to fit, doing away with the space issue we had when we wanted to fit a Fox Float-X to our bike. Another point we raised was that the taper headtube should also evolve from the external 1 1/8” and 1.5” cups on our frame to use the same ZS44/ZS56 semi-internal type headsets that have fast become almost standard across the industry. This is now standard on all new frames and allows for better internal cable routing as well as easing headset sourcing.

A final point we found was that, while absolutely fine for the original trail bike aims of the F-11, the shock mounting hardware and the lower linkage designs were both at their very limits when used for the bigger courses and we suffered a couple of bent bolts. It’s a point we’ve discussed at length already with Pawel at Zumbi and there are redesigns in course to eradicate these weaknesses. We believe the lower linkage issue to be down to the additional twisting forces brought upon it by the longer front end and the riding that we were therefore able to put it through. As with any small company development is ongoing and we certainly have no hesitation in believing that all these niggles are going to be resolved.

Pinkbike's take:

| If you're looking at an enduro bike then you could do a lot worse than look to Poland and Zumbi with their F-11. In standard guise you get a bike with an efficient and highly capable rear end. Add in the option of custom geometry and a whole new world opens up along with a number of aesthetic changes which all combine to really produce an individual bike. Do you want an individual bike though, or would you prefer to go for tried and tested? If it's the former then the Zumbi offers a very credible option that can be tuned to cater for a wide range of riding, whether your focus is on the gravity assisted side of enduro or a more all-round bike that can ride all types of terrain, all day, every day. Given the number of options available, including the introduction of 650B, it's safe to say that there should be plenty of scope for you to get the exact bike you want.- Alasdair MacLennan |

dissabte, 10 de maig del 2014

Copa del Món d'Enduro a Chile

Aquí teniu un bon vídeo de resum de sa Copa del Món d'Enduro a Chile! Pegau una ullada i no vos perdeu es trams de'n Cedric... Espectacular ;-)

DirtTV: Enduro World Series | Round Up Edit a Mountain Biking video by dirt

DirtTV: Enduro World Series | Round Up Edit a Mountain Biking video by dirt

Subscriure's a:

Comentaris (Atom)